Art Apéritifs with art critic and professor, Robert Pincus

A charming conversation on art journalism in the 80s & 90s, meeting Roy Lichtenstein and the case for contemporary art in San Diego

21st & 18th reports on the pulse of culture, then & now. Covering topics of art, history and fashion and featuring interviews with voices in fashion and leaders in the arts. Follow 21st & 18th (@21stand18th) on Instagram.

Written by Lauren Lynch Wemple (@lolynchwemple), you can expect two articles per week.

Today on it’s Art Apéritifs, the one where I interview leaders in the arts sector and discuss what they do, why and how they got there. Usually we find ourselves in discussion with museum leaders from around the world, but today I have a treat for you: a conversation with a veteran art critic and professor, Robert Pincus.

I met Robert through a 21st & 18th Patron who is local to San Diego, shoutout to Karen <3, who originally met Robert as a student studying for her master’s degree in art history - isn’t it lovely when chapters of life collide?

When Robert and I met, I was feeling overtly confident in where I was going with 21st & 18th and life and even possessed some haughtiness regarding my current literary queue whereas today, re-reading our conversation from March, I find myself in a rut. Is rut the correct word? In any case, what I find fascinating is that my conversation with Robert made me feel the same today as our first meeting. I left our connect in March feeling smart, ready to adapt to feedback and inevitable personal and professional hurdles but mostly, I was excited. Excited to try, put myself out there, write, create, travel and meet new people, feelings I desperately needed to feel today.

I hope you’ll enjoy my conversation with Robert and float into your day with a burning excitement for something, anything, and if you take anything away from this read let it be the reminder that art and culture are all around us, in big and small cities in big and small ways - go looking for the art and ask questions when you find it.

Del Mar, California, 8 March 2024

LLW: It's myself and Robert Pincus in conversation. Robert, would you introduce yourself to our Readers?

RP: Introduce myself? I am Robert Pincus. I am an art critic, also an art educator. Love writing, love teaching and that's why I do both. I know that's short and pithy…

LLW: That’s perfect, thank you.

I'm fascinated by you, Robert, because you’re both a teacher and an art critic and when I interviewed John Marciari (of the Morgan Library) and Derek Cartwright (of the Timken Museum of Art) for Art Apéritifs we discussed how the ‘art historian’ career path comes to a crossroads when curators or professionals in the art sector choose museum work, teaching or scholarly work, but you’ve managed to do it all. Would you talk a bit about your road to teaching and being a professor?

RP: My goal when I went to grad school was to be a scholar, writer and a teacher.

LLW: What's a scholar/writer?

RP: Well, in other words, I was going to write longer pieces such as articles, books. Even when I was in grad school, I published a couple of articles in academic journals.

LLW: Impressive.

RP: I was always interdisciplinary. I'm not a straight ahead art historian, my training is probably what an art historian would call unconventional.

LLW: Same. <laugh> What did you study while at university?

RP: I enrolled to get a master's degree in American Studies from University of Southern California1 because I was interested in the idea of interactions between different periods of artists and writers in American literature and American art. American Studies allowed me to do both.

LLW: And all of those topics inform and impact each other. I always say context is critical to understanding history and art. Who were some of the American artists you focused on while doing your master’s?

RP: I decided to do my master’s thesis on an artist named Ed Kienholz2, as I was interested in LA’s art history and felt that it hadn't been told very well. [I was lucky to have had encouragement from] a professor who specialized in modern and contemporary art at USC, Susan Larsen Martin, who had done quite a bit of writing about contemporary art in LA and she encouraged me.

Kienholz is an artist who's really interesting and there was very little written on him at the time except some catalogs. There was another subtext to it, his art is quite narrative and literary, [he was] pioneering sculptural environments, which brought my literary skills into the research.

LLW: Given your multifaceted background, I’m curious, what did you gravitate toward most?

RP: My interest was always in critical writing, whether it be doing it in a scholarly way or in a popular way…and my USC thesis mentor recommended I start writing art reviews…She put me in touch with an editor at Artweek, a West Coast art magazine - which is now defunct.

LLW: How cool.

RP: The editor gave me an assignment and I wrote a couple of reviews. However, I will be honest with you, I never thought about being an art critic as a full time endeavor.

LLW: Did it seem like a job that was too good to be true?

RP: It's a great activity, and I thought it could be part of my portfolio of things I do, but I was forging ahead [with my graduate studies]. A while later, while finishing my master’s thesis, I got a call from the Los Angeles Times, from Suzanne Muchnic3, the second critic there at the time, and she asked if I would be interested in writing reviews for them. William Wilson, the senior art critic, then seconded her offer to let me start writing some reviews for them.

LLW: Were you reviewing whatever was happening on the art scene in LA? And how often were you writing these reviews?

RP: I was the part-time critic, which meant they would give me assignments and I would write two to three gallery reviews that would run every Friday.

LLW: That’s a lot of work each week.

RP: To give you a fuller picture, I was teaching, because teaching was part of my grad school education, taking grad school courses and trying to do my art reviews each week. All of this started about the time I enrolled in my PhD program in English at USC.

LLW: Certainly a lot was on your plate.

RP: <laugh> It was a lot.

LLW: In terms of being an art critic, how does that work? Would you go to a gallery, look at the art and decide if it’s good, bad or ugly?

RP: I had to figure out what kind of reviews I wanted to write. I knew it should be partly descriptive and partly opinionated, because you have to give people a description of what you're writing about as they wouldn't print photos with all of the reviews. Remember this was an era where nothing was online yet; it was still print only.

LLW: Of course, so you're describing in addition to evaluating.

RP: Right. All in a few column inches.

Read one of Robert’s art reviews from January 1985 in the Los Angeles Times Archive, here.

LLW: <laugh> Almost like a long form Instagram caption that has to be quippy, smart, accurate and interesting…

RP: Plus, give some historical context and an opinion. Also, these reviews mattered to more people then because there wasn't social media or online content [for them to consume].

LLW: Right! The art critic’s column was the voice when it came to reviews on art, galleries, culture.

RP: Because I was part-time I often got assigned the reviews the more senior critics didn’t want to do, but there's a silver lining to that which is you got to review emerging artists. For example, they sent me out to write about Mike Kelley4, who became a very prominent artist in his lifetime, and I wrote about one of his first shows.

LLW: How fun to be on the discovery end of contemporary art. How long did you work as an art critic?

RP: When I finished my graduate and PhD work I was at a crossroads and thought, “Am I going to keep going with academia? Or am I going to continue down the criticism route?” It was an interesting dilemma.

LLW: And, what did you choose?

RP: I chose the art critic route after getting offered a full-time job.

LLW: One of my main goals for Art Apéritifs is to help people understand that you can do and learn about a lot of things, you do not always have to choose one path, one subject, one career - your professional journey is a great example of that.

RP: There's a balance. [In my case] it was a little scary because you don't know what job is going to be there. It just so happened that these opportunities sort of came together, but interestingly I didn't define myself solely as an art critic, which left the door open…

LLW: To clarify, you worked as an art critic at the LA Times and then the Union Tribune. What was happening in your academic career when you started as an art critic?

RP: When I got my first full time art critic job I had not yet written my dissertation. [For my dissertation] I had decided to focus, again, on the work of Ed Kienholz which became a project on Ed and Nancy Kienholz5 because they were really co-artists. At this time, I had done the research and had Ed and Nancy helping me…They were just incredibly gracious throughout the project.

LLW: How cool to be writing about and researching artists and have them live, in-person to answer questions and pull back the curtain on their work.

RP: They really cooperated with me.

LLW: Out of curiosity, how long is a dissertation?

RP: [While writing it] I had wonderful advice; my chair, Jay Martin, told me to write my dissertation as a book. [It ended up being] about 160 pages.

LLW: To ensure we’ve got the full picture, you have this new full-time job writing during the day and you're writing your dissertation in the evenings. That's an insane amount of writing.

RP: It was insane, but I knew I wanted to finish. Plus I had a motivation for it to be a book…There was a very good publisher interested in it. That didn't mean they would definitely do it, but UC Press was genuinely interested.

LLW: Busy man! That's cool.

RP: They eventually ended up publishing it.

LLW: Do you like writing? And have you ever got to a point in your life where you were exhausted by writing?

RP: I developed stamina and a bond with it. I can't say you enjoy every time, every minute when you're writing, [back then] it was a little painful to be writing at night when I wanted to be sitting back and not doing anything, but I knew I wanted to write this. I was inspired to write it and I felt like I was adding something to history because there were no books on the Kienholzes.

LLW: Paving a new contemporary art lane for them.

RP: Funnily enough it was just published as an ebook…UC Press has been selecting some of their catalog and re-publishing them out as eBooks.

| Click here to purchase Robert’s eBook on Ed and Nancy Kienholz

LLW: Amazing. How long did you work as an art critic at the Union Tribune?

RP: 25 years until they basically eliminated the job.

LLW: Wow.

RP: From then on the art coverage at the publication became kind of spotty.

LLW: During those 25 years at the Union Tribune, did you travel all over to see shows and meet artists?

RP: When I took the job they were quite ambitious. They wanted the coverage to focus on San Diego, but to be in a bigger context. I'd go up to LA often to write about the bigger shows and a couple times a year I'd go to New York for the Whitney Biennial6, and other big retrospectives.

LLW: Did you find that Tribune readers enjoyed content about contemporary art?

RP: After a period of time writing there, I realized it wasn't necessarily the entire readership of the paper. and You wanted to appeal to people who knew a lot about art, as well as the people who knew just a bit. The readers might know who Jasper Johns is, but think, “Why should I care?” And I wanted to explain why art like his might be worth caring about.

LLW: Yeah, totally.

Out of curiosity, do you have a favorite artist or show memory from your time as an art critic?

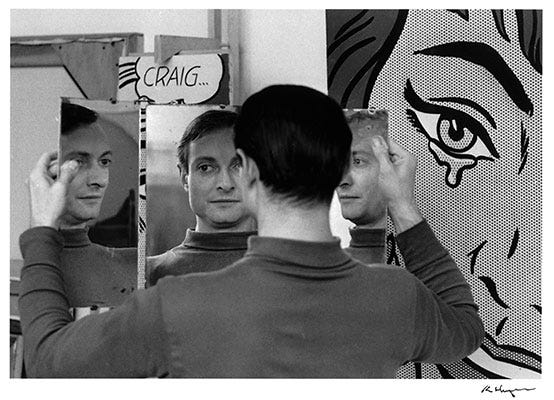

RP: When you meet an artist it reinforces something you know about their work. I'm sure you know the work of Roy Lichtenstein7, the pop artist, right?

LLW: Yes, I do.

RP: I met him very late in his career.

He had a print retrospective up at LACMA8, and I called up Sid Felsen who runs Gemini9 and asked if I could interview him. [I ended up meeting him] at Gemini, where he was making prints, of course in the Lichtenstein style, using Hokusai10 prints as his source. They looked like his version of classic Japanese prints, Mt. Fuji and other iconic sights. Lichtenstein was showing me a couple of these images he was making and said, “Look, I can turn anything into a Lichtenstein.” He was laughing, he thought this was the funniest idea, how art from any period could be done in his style, and this premise seemed to be the essence of his art..

LLW: You were right there in person with Roy Lichtenstein, hearing from him about his process and work. Incredible!

RP: He had a comic sensibility, you know what I mean? He wasn't a tortured artist in the Romantic mold. It seemed to me like he was a happy fellow.

LLW: When you experience moments in life like that, as someone who has studied and taught art history, how do you feel?

RP: It’s a little unreal.

LLW: Is it dreamlike?

RP: No, it reminds me that these artists are not icons. They're people. You can admire them for what they did and do, and yet at the same time you realize that they see themselves as creative people that keep doing what they're doing.

LLW: Liechtenstein seems like a person who probably didn't have much ego.

RP: He was a pretty unpretentious person.

RP: Ed and Nancy were a lot of fun also, it was memorable spending time with them, Ed was a bit of a prankster.

LLW: <laugh> When did you start teaching in San Diego?

RP: I wasn't planning on teaching, but the first year I got to San Diego a professor I knew at San Diego State University was going on sabbatical and asked me to teach her grad class in theory and criticism. It was a little crazy to do because I was writing my dissertation and working at the Union Tribune when I accepted this class to teach.

LLW: You seem like a person who thrives on having a lot of things on your plate.

RP: <laugh> I did then and maybe I still do. Anyway, I taught that class at SDSU11, enjoyed it, and a couple years later they asked me to teach another class. Then in the late 90s USD12 approached me about teaching a course. I really enjoyed getting back into teaching, and later, when my job got eliminated at the Union Tribune, I had to redefine myself again. I knew I would still be a writer, but I wanted to teach more.

LLW: Have you always taught art history?

RP: Yes, but not only art history. One of the classes I really enjoy teaching is a class designed for USD, which is artists’ stories in art history, film, and other media. I emphasize the idea of thinking about the art we're looking at and encourage students to consider what the artist’s story is that inspires and informs their work..

LLW: Makes perfect sense for your background. <laugh>

RP: And then, a few years ago, around 2016, I'm talking with the chair over at Cal State Long Beach13 and she was looking for somebody to teach a class called ‘Writing for Artists’ and asked me if I'd be interested. It was then that I started teaching that course at the grad level, and eventually for undergraduates too, at Long Beach. I also teach ‘The History of Western Art Theory and Criticism’ there, which is inspiring.

One of my favorite things to do with art history classes is to have them read short stories about artists.

LLW: Any good examples?

RP: Students really love “The Color Master” by Aimee Bender14, a contemporary writer. It's very quirky, very engaging and says as much about color as any theoretical writing. It riffs off of a fairytale called Donkey Skin.

LLW: It seems to me, from hearing you speak, that you love teaching.

RP: I enjoy it. I love being around students. It'll sound like a cliche, but it does make your mind younger, because you aspire to relate to people who live in another world than you do.

LLW: That's a great point.

I wanted to ask you, as we're both local San Diegans, are there any San Diego artists we should be talking about that people might not know?

RP: Well, I wonder if people still know about Manny Farber15.

LLW: I'm not familiar with their work.

RP: Manny Farber was a renowned film critic, but he pretty much gave up writing film criticism when he came to San Diego to teach at UCSD. He taught a film class which was apparently legendary for being both difficult and stimulating. But what Manny really wanted to do was concentrate on his painting.

LLW: Oh really?

RP: When he retired from UCSD in the late 80’s, he really did concentrate on his art. He's a pretty amazing painter. Though he never quite got his due, he did get a good deal of recognition. Mark Quint showed him all the time and still does exhibit his work..

LLW: You learn something new everyday.

RP: He's an interesting case.

LLW: Contrary to popular belief there is a lot of culture happening in San Diego!

RP: San Diegans don't really know our art history very well. You know?

LLW: We do not.

RP: The good painters that have been here and worked here, but San Diego tends to be overshadowed by LA.

LLW: Totally. For our Readers, which San Diego galleries would you recommend they visit or have on their radar?

RP: Currently, Quint16 has always been a steadfast place to see contemporary art and consistently has notable work . He showed Robert Irwin17 too, who sadly died last year. Interestingly, I don't know that Irwin has ever been seen as a San Diego artist, even though he lived here for decades, because he made his name as a light and space artist in Los Angeles first.

Aside from that there's Joseph Bellows18, a really good photo gallery. He shows a lot of great historical and contemporary work. R.B. Stevenson19 is a good painting gallery and then Bread & Salt20 has become a big hub for a lot of shows, they have multiple spaces down in Barrio Logan. There are other spaces throughout the county and the Institute of Contemporary Art has venues in Balboa Park and Encinitas.

LLW: Great recommendations, thank you.

More personally, anything you’re reading right now that you would recommend to Readers?

RP: Right now I'm reading Upton Sinclair21, The Jungle.

LLW: A classic.

RP: I've never really read it. I knew it by reputation. Sometimes I want to read books that I feel like I need to revisit.

LLW: I love doing that.

RP: It is an amazing novel about immigrants coming to the United States and having an awful time of trying to assimilate, living in poverty and figuring out how to navigate a big city. I see it as more of an immigrant novel, which is sort of interesting given the contested situation surrounding immigration at the moment. It’s a bit of a downer, but a moving one.

LLW: Thinking outside of galleries, what is your favorite museum?

RP: Favorite museum?

LLW: Yeah. Anywhere in the world.

RP: I can't say that I have a favorite museum because that would be too hard. I like too many museums. <laugh>

For the way you experience art The Menil Collection22 is one of the best in the world, just in terms of looking at a collection. I could name four or five more but the obvious one is the Museum of Modern Art23. In terms of looking at 20th century art, there is no better place than MoMA.

LLW: Their experience is wonderful. You can find moments of solitude and you can feel the energy of the art viewing it with loads of other people - somehow both experiences are energy giving.

RP: Thinking about European museums, to me the Musée d’Orsay24 is phenomenal. To experience all that art first hand…

LLW: The first time I walked it through the d’Orsay I was overwhelmed by the number of works of art I was seeing live in one place that were in my art history textbooks.

RP: Another museum that is a great experience is the Tate25 and seeing its Turner26 paintings.

LLW: Completely agree.

RP: I mean, talk about sublime.

LLW: Perfect description of the Tate Britain Turner experience.

RP: They are sublime in the sense that they are almost overpowering.

LLW: I found Turner’s work more interesting after learning more about what he was like as a person…

RP: Yeah, he wasn't a terribly pleasant person.

LLW: From the history books it sounds like he was a bit of a curmudgeon.

RP: <laugh> But he had this inner sensitivity to the world. I always tell students, the artist and the art can be very different. A person you would find unlikeable can create the art that you love the best, or vice versa.

LLW: That's a great point. Again, context gives art additional dimension.

RP: Locally, I have always enjoyed the scale of the Timken27. I like little museums - as well as big ones - where you can experience four or five paintings at a time. There was a really interesting curator and museum director, Henry Hopkins, who said that his favorite museums were often smaller ones, where he could visit for an hour, spend time with some art and not be overwhelmed.

LLW: I can relate.

RP: God knows I love the Met28, but feel overwhelmed the minute I walk in.

LLW: And you wait in lines to see art?

RP: After that you just want to escape to the Frick or the Morgan…

LLW: I always ask this on 21st & 18th: What are you currently obsessed with?

RP: Obsessed with…

LLW: Could be anything, a person, place, time period. What can you not stop thinking about?

RP: I don't know if I'm obsessed with anything right now. <laugh> But I'm slightly obsessed with doing more chapters in a slow going book that I'm working on.

LLW: Okay.

RP: I can give you the working title, it's called Lucky Quest.

LLW: What is this book about?

RP: Learning from learning from artists, writers, mentors, and other art critics.

LLW: Very interesting.

RP: What I've learned over time doing what I do. I don't want it to be a strictly traditional memoir, but episodic chapters about interesting moments and people that have helped me learn about what I do.

LLW: I like the idea of that format. Sounds enjoyable to consume.

RP: I've only written three chapters so far.

LLW: How does one write a book?

RP: I have a concept and keep following it intuitively. I don't have a rigid outline structure, but I have chapters in mind that will change as I keep working on the project. I'm a little obsessed with that, but I don't get enough time to work on it, which is probably partly why I’m obsessed with it.

LLW: Last question, what advice would you give to someone who wants to be a writer or explore the professorial path you’ve taken?

RP: I would tell them to pursue writing about the arts only if you really have a passion for it or an obsession with it. You will get a lot of discouragement along the way, but if you're lucky enough to have people encourage you, like I did, then do it. But don't expect it to turn into a job; you may need to do another job entirely to support your work in the arts.

LLW: That's important. If you love something and are good at it, you can do it, but it doesn't have to be everything for you professionally.

RP: And it may not be possible. It's difficult nowadays because there's not enough opportunities for writers in general.

LLW: That's a very realistic perspective that people need to hear. Don’t be afraid of doing more than one thing in order to make space for the work that feeds your soul and mind.

It will be no surprise for any of you who have made it this far to hear that interviewing and working with Robert on this feature was fun and energizing. His decades of experience teaching, writing and editing really shone and served as a reminder for a struggling writer to keep at it despite the constant pull to give up.

Robert, thank you for your time and joining us in conversation on

, never stop teaching (or critiquing the art).University of Southern California or USC in Los Angeles, CA

(b. 1927 - d. 1994) Ed Kienholz was an American installation artist and assemblage sculptor whose work looked critically at aspects of modern life. From 1972 onwards, he worked with his artistic partner and fifth wife, Nancy Reddin Kienholz.

(b. 1940) Suzanne Muchnic is an art reporter and art critic who worked at the Los Angeles Times for 31 years before her retirement in 2009.

(b. 1954 - d. 2012) Mike Kelley was an American artist whose work encompassed found objects, textile banners, drawings, assemblage, collage, performance, photography, sound and video. He is noted as one of the most influential artists of our time. Learn more about his work on MoMA’s website.

(b. 1943 - d. 2019) Nancy Reddin Kienholz was an American mixed media artist who worked in installation art, assemblage, photography, and lenticular printing. After the sudden death of her artistic partner and husband, Ed Kienholz, she continued to produce art until the end of her own life.

The Whitney Biennial is the longest running survey of American Art and was initiated in 1932 by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Learn more here.

(b. 1923 - d. 1997) Roy Lichtenstein was an American pop artist who defined the art movement in the 1960s alongside Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and James Rosenquist. Lichtenstein is known and most recognized for his comic strip looking prints.

Sidney B. Felsen is one of the founders of Gemini G.E.L. an artists workshop and gallery based in Los Angeles, CA and founded in 1966. Learn more about Gemini here.

Referring to Katsushika Hokusai (b. 1760 - d. 1849) was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist of the Edo period known for his paintings and wood block prints of Mt. Fuji and, most iconic, The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

(b. 1917 - d. 2008) Manny Farber was an American painter and film critic known for his distinctive prose style and set of theoretical stances which had a large influence on recent generations of film critics and underground culture. Farber moved to San Diego in 1970 and passed away at his home in Encinitas, CA in 2008.

(b. 1928 - d. 2023) Robert Irwin was an American installation artist known for his innovative works that explored the effects of light through architecture and space. Learn more about Quint’s show on his work here.

(b. 1878 - d. 1968) Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. was an American writer, muckraker, political activist. While he is most remembered for his almost 100 books, interestingly, he was also the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California.

The Menil Collection is a museum and campus dedicated to art in Houston, Texas. Learn more and plan your visit to the 30 acre institution here.

Robert is referring to Tate Britain, a fantastic museum housing the work of British artists, and between Tate Britain and its other museum counterparts, Tate Modern and Tate St. Ives, houses a collection of British art from 1500 to present day. Learn more and plan your visit here.

(b. 1775 - d. 1851) John Mallord William Turner was an English Romantic painter, printmaker and watercolorist known for his expressive, aggressive and imaginative landscape paintings.