Art Apéritifs with Nancy Ireson of the Barnes Foundation

An interview with Nancy Ireson, Deputy Director for Collections and Exhibitions & Gund Family Chief Curator at the Barnes Foundation

21st & 18th’s Newsletter is comprised of a variety of segments. This segment, Art Apéritifs features interviews with leaders in the art industry from around the world. Subscribe to 21st & 18th to read Art Apéritifs each month.

San Diego, California

When my husband, Wemple, asked me on our first date he had one secret destination in mind: The Barnes Foundation. In 2015 when I was overwhelmed by life, school and figuring out my graduation plans post undergrad I escaped to one place: The Barnes Foundation. No matter when or where, should you come into contact with a Philly local and ask for their go to sites in the city, the Barnes Foundation always graces the list.

This Art Apéritifs interview is about the Barnes Foundation, if you hadn’t already gleaned, and is made interesting and worth your time to read because of the person featured: Nancy Ireson. For those Readers who are unfamiliar with the Barnes Foundation it is a museum in Philadelphia that is home to one of the world's great collections of modern European paintings, with numerous works by Renoir, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Van Gogh, and Modigliani. Impressed? Yeah, us too.

Before I met Nancy, I was giddy for a couple of reasons: 1) The Barnes Foundation is probably my favorite museum in the world and 2) It’s an exciting privilege to capture a glimpse of what life is like at the Barnes, understand why Nancy does what she does and how a Brit came to be in Philly.

I hope you’ll enjoy and be inspired by my conversation with Nancy. Let us know your thoughts in the comments, on Instagram or write to me: lauren@21stand18th.com.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

20 February 2024

It is so cold in Philly today and it feels shocking to the system coming from sunny San Diego. Despite the frigid weather and naked trees dotted around Rittenhouse Square, I am very happy to be visiting Philly. Not only is my father originally from Philly but my husband and I (plus many other family members) both attended Villanova University just outside the city. Being in Philly feels like coming home in some ways.

Despite my adorable personal connections to this city, I’m here for one reason: to connect with and interview Nancy Ireson, who is currently the Deputy Director for Collections and Exhibitions & Gund Family Chief Curator at the Barnes Foundation.

Nancy and I meet after work on a Tuesday at Parc on Rittenhouse Square. The lighting is as it always is at Parc, dim and gooey but still flattering and there’s music and sounds of flatware and glasses clinking taking up space like a third guest at our table.

LLW: I am interested in your pathway to the Barnes Foundation. You have worked at a lot of incredible institutions, some of my favorites: The Morgan, Tate, Art Institute of Chicago! What has the red thread been in your roles at each of these places?

NI: I've been really lucky in that, in each of the places I’ve worked there's always been something to learn. I feel that I’ve grown in each institution, delivering some great projects and meeting some wonderful people. I've been part of incredible teams over the years.

LLW: These are some of the greatest institutions, literally, in the world for the arts. When you look back, is it your network that has been really important? Or is it as simple as doing the best work you can and being at the right place at the right time? Or a little bit of everything?

NI: It's a little bit of everything. I’ve often found opportunities – including my current role – because colleagues have recommended me to their peers – I take that as a great compliment because it means that you've left a good impression! People have seen your work, liked your work, liked you as a person. I didn’t enter the field with a network but, over time, doing your best can help to build one. It’s a long game…which is important to remember.

LLW: Taking us in another direction, where are you originally from?

NI: London is the place that I identify with the most because it's the place that I lived the longest. My family moved around the UK quite a bit when I was a child, but I moved to London to study when I was 18, and worked there for several years after I left university.

LLW: Living in a city like London, do you remember when you fell in love with the arts? Would you talk to me a little bit about the moment?

NI: I was lucky that my parents both liked art. They met when they were students, and both had history degrees. I think that my mum would've liked to have been an art historian <laugh> and she always used to take me to exhibitions. It was just something we did. One of the first exhibitions I saw was a Renoir1 exhibition in 1985, at the Hayward Gallery.

LLW: Oh really? That makes a lot of sense. Look at you now2!

NI: It's funny because you always think you make your own destiny, but then the penny drops… <laugh>

LLW: It's that invisible hand that's not really invisible at all.

NI: Today, I really do understand how for a lot of visitors, there are many barriers to feeling comfortable in museums and galleries. I was really fortunate that museums were always a place I felt comfortable. A gallery visit was a nice day out.

LLW: It was regular enough to be part of life. Of those early years exploring museums and galleries, were there any specific museums you felt at home in?

NI: The National Gallery3 was the mothership

LLW: <laugh>

NI: When I [eventually] got a job there, I remember being very excited. That was a ‘pinch myself’ moment. I had a fantastic boss there, Christopher Riopelle, who still works there and who I still admire hugely. He's a fantastic curator and taught me in very practical ways, like trusting me to oversee a rehang when a work went out on loan. There is nothing like learning by doing.

LLW: How do you feel about living and working in Philly?

NI: It's a great city. I love that there's a strong arts community here and that, because it’s relatively affordable, artists still live and work in town. Institutions here can work together safe in the knowledge that what's good for one Philly arts organization is good for others. It's very collegial.

LLW: I love Philly. It’s great to be back here - I went to university nearby - but Philly just has a welcoming vibe. I like the version of myself when I’m here wandering around the city’s neighborhoods.

NI: We don’t have to be as competitive as it might be in a bigger city, and that's a real strength. <Nancy pauses> It’s also very well connected, which helps us to grow our audience and develop new partnerships.

LLW: By ‘partners’, are those artists? Or academics and researchers?

NI: All three! For example, today I was speaking today with our exhibition designer, he's based in Minneapolis and is flying in on Wednesday to talk about one of our upcoming shows. Later, I was on the phone with a curator we’re working with, who is Austrian and based in the UK…We have a great network of people bringing in different perspectives, and that variety feels appropriate for a city that has often welcomed transplants. I always feel welcome as an Expat.

LLW: There's sort of porousness to Philadelphia when it comes to culture, background and nationality.

NI: That's a good way of putting it. In Philly, people aren't necessarily surprised that you have a foreign accent. That's business as usual.

LLW: One time I was here in Philly in an Uber and the driver was a Frenchman. As we were driving, he was explaining how he recently moved to Philly and chose Philadelphia because someone in his family lived here. I asked how he liked it and he said, “To me, Philadelphia is the most European of the cities that I've been to in America.” That was really interesting, and every time I’m here I think about that conversation. What do you think of his sentiment?

NI: I think he’s right! Philly offers the best of both, in that you have the walkability of a European city, but you also have the vision of an American city. There's a sense of possibility, which is always something I associate with the US… A future-facing attitude.

LLW: Hope is very powerful here. <pause> I love Philly and I love the Barnes Foundation. The collection and experience of the Barnes is incredible. Let’s dig into the Barnes and start super general: Would you tell me a little bit about the founder of the Barnes Foundation, Dr. Albert C. Barnes?

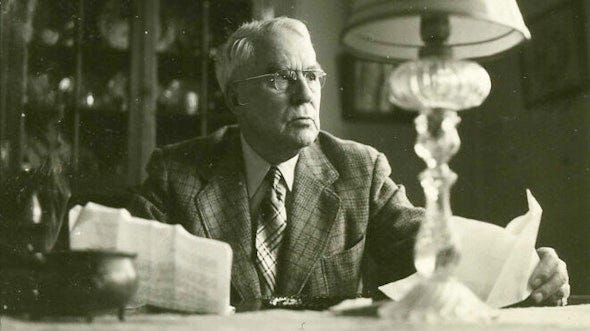

NI: He has a pretty surprising story. He was from a very blue collar background, but was brilliant. He did very well at school and was a medical doctor before the age of 20 - he qualified really young. Interestingly, he didn't actually practice medicine, but became a chemist, and went off to Germany to do his graduate work.

LLW: Certainly, impressive.

NI: And he went on to co-invent an antiseptic that was put into the eyes of newborn babies…

LLW: Ah, so that's where the money comes from.

NI: <Nodding> That’s where the money comes from...The thing that really stands out in Barnes’ story is that: yes, he was super bright academically, but he was also an incredibly good businessman. He made the right moves at the right time and, by the time he was 40, he was a very wealthy man.

LLW: He was a man of many talents. Okay so he’s got money, is super smart and about 40 years old. What next?

NI: At this stage in his career, he asked an old high school friend, artist William Glackens4, to go buy art in Paris on his behalf and gave him $20,000 to do so.

LLW: Alright.

NI: Barnes had already tried to buy a few things, but it’s really when he asked Glackens to do some shopping on his behalf that things took off. Glackens buys a Van Gogh5 and a Picasso6 and a Monet…the list goes on!

LLW: I mean, fantastic use of $20,000. <laugh>

NI: This is in 1912.

LLW: I’ll adjust for inflation in the article7.

NI: Even then, not a bad investment! After these purchases, he really gets the bug [for collecting]. He travels to Paris himself and begins meeting artists. Over the years he makes some astute business decisions. For example, he bought dozens of works from Soutine’s8 studio in 1922.

LLW: How forward thinking, as at the time people were basically grossed out by Soutine.

NI: True. But by allowing the works to go on show in the US, he helped to build the artist's reputation in this country. And when he had done so, he sold some of those works on to other collectors…

LLW: Wow. He's already thinking of art as both collectible and an asset with a market.

NI: He occasionally would do things like see what's happening with exchange rates to understand if he should wait to buy something. It's a buyer's market as well, not many people had the wealth at their disposal that he did. Also, he wasn't buying contemporary art necessarily. He was buying work that was a little bit beyond the taste of a lot of institutions, which created a good opportunity to really make a mark.

LLW: Talk about making a mark. Today the collection of the Barnes Foundation is iconic. I’m curious. What was Dr. Barnes’ personality?

NI: I think he was a complex man. He had a vision, and there are moments of brilliance in his aims, specifically his desire to make art available to everybody at a time it really wasn't. He would even stop production in his factory in West Philadelphia for two hours every day, and his employees – Black Americans who had limited access to education – would be paid to learn about art. The Cézannes9 and the Renoirs, so many works from the collection played an active part in his teaching program.

LLW: That's very cool.

NI: It is! And he worked with John Dewey10, and together they explored how becoming visually literate might help a person become more active in society. That’s something I find really fantastic – that in 1920s America he was absolutely adamant that the country should be more equitable. Within our exhibition program we really try to honor that intention, by ensuring that our programming is inclusive.

LLW: I agree, it’s forward thinking. Makes me proud.

NI: Yeah. It’s interesting because you look at the hang11 and he was trying to put things from different times, places and peoples, and within that some of the biases at the time come out.

LLW: What would be an example? Would you talk a little bit more about that?

NI: Barnes displayed African works alongside paintings and sculptures by European Modernists, showing how West African masks inspired Modigliani12 and Picasso. While the connection was well-meant – Barnes wanted the African Diaspora to experience African works, and to see how they had helped to shape Modern art – his display does not acknowledge how ritual objects functioned in Africa.

to highlight the links between collecting and colonialism.That's one of the reasons we worked with Isaac Julien13 to commission Once Again…Statues Never Die14, to highlight the links between collecting and colonialism.

LLW: Totally - context is critical.

Thinking about how the artworks in the Barnes collection are physically laid out, for someone who is visiting the Barnes Foundation for the first time, how would you recommend they approach your collection and space?

NI: If you can, it is worth seeing it over a couple of days because it takes a lot of time. Quite often people don't realize there is a second floor, because they are so overwhelmed by the first floor. If you have a limited amount of time, be drawn by what speaks to you. Don't try and see everything. That's good advice for visiting any gallery. Walk into a space and think, what do I want to look at? It's better to have a few really meaningful minutes with something that attracts you personally than to try and tick boxes…That said, it would be hard to imagine going to the Barnes without seeing The Joy of Life15 or the ‘greatest hits’ in gallery one, that include Seurat’s16 Poseuses17!

This is a good moment to remind you to visit the Barnes Foundation next time you’re in Philly OR play it like me and for those in the Northeast take a day trip, powered by Amtrak, and enjoy the collection. Learn more about visiting and the Barnes’ membership program here.

To further entice you, the Barnes also has an excellent program of exhibitions on and upcoming:

Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me through May 18

Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes, June 23 – Sept. 8, 2024

Mickalene Thomas: All About Love, Oct. 20 – Jan. 12, 2025

LLW: Are there any works in the Barnes’ collection where you look at it and are in awe?

NI: For sure. There are so many and, in a way, it depends on what mood you're in. It's a bit like music. You seek out different tracks depending on how you're feeling. One painting I am absolutely passionate about is Seurat’s Entrance of The Port of Honfleur. It’s incredibly atmospheric; the muted colors and gentle light effects really convey how it feels to be by the water.

LLW: I get that, artworks that force you to pause and transport you. The whole museum really feels like that. Museum isn't the right word for the experience that is the Barnes, you know what I mean? It's obviously a museum, but I don't think of it like that.

NI: It's an immersive

LLW & NI: Experience. <laugh>

NI: It is!

LLW: The Barnes has an invisible energy from Barnes himself, all of your team, all the artists whose work hangs within the space, and it can be overwhelming. With that, your tip for seeing it over more than one day or if you only have a finite amount of time, to go where you feel called - that's critical. There is so much goodness at the Barnes.

NI: And recognize that you don’t have to follow a formula. What do you need that day? Do you want to be challenged or comforted? Energized or still?

LLW: This is a random question but are you writing anything or doing much publishing at the moment? I know writing has been a big part of your role as Chief Curator, but as Deputy Director does that change?

NI: I’m still doing a fair amount. Last year, with James Claiborne18 I co-curated a William Edmondson show19. We co-wrote a piece for that. Also, I've been taking an MBA recently, so most of the writing I’ve been doing has been about business.

LLW: Really! How do you like that?

NI: It's interesting. It’s a good contrast to my humanities training. Some of the modules have been harder than others!

LLW: Was an MBA just something you decided to do?

NI: I felt that it was really relevant to my work. The arts and arts organizations do not exist in a vacuum. I was curious to have some formal education in topics that include marketing and finance.

LLW: It’s a great reminder that we can study both and working in the arts requires both types of thinkers. Speaking of such, you’ve worked at a number of incredible institutions around the world, so we must ask you for advice. What advice would you give to someone who is studying art history or considering a career in the arts?

NI: Don't get disheartened.

LLW: That's important.

NI: It's a very tough business to break into and most people must go through that pain barrier. It's a lot easier to look at it from the other side than it is to be facing it, but you have to keep chipping away at it, and make the most of the opportunities that come your way. Be keen to learn and open to the unexpected.

LLW: <Nodding>

NI: And be patient. I struggled with that!

LLW: It's difficult to be patient in this day and age as we see everything seemingly happening on Instagram in the blink of an eye.

NI: Well, other industries have different paces. After you graduate in the arts, chances are that you’ll see people you knew at college forging corporate careers at lightning speed. If you feel like you haven't got off the starting blocks, that is totally normal.

LLW: I remember feeling like that. It was scary to feel left behind or as though I was losing the professional race.

NI: I don't think many people in the arts realize that it takes a strong personality to tough it out, and that you simply can't draw those comparisons with for-profit careers. Comparing timelines or lifestyles is unhelpful…it’s a different business.

LLW: Sure..

NI: Know you're doing it for the right reasons, as well. I worked in the commercial art world before I went to do a PhD.

LLW: Did you like it?

NI: No, I didn't enjoy it, but I'm glad I did it because it changed the way I thought about the art world. <Nancy pauses> Commercial experience helped me to understand that artists need to make a living.

LLW: Yeah.

NI: There are often very logical reasons why artists do something multiple times or make certain decisions [across their career]. They have bills to pay, lives to lead…. It's important not to see these things as siloed. It's an ecosystem.

LLW: Totally…Another question, and this is a fun one: what is your favorite museum?

NI: Wow.

LLW: If you have one.

NI: Well, I mean a lot of the ones I worked in actually. The Barnes, the National Gallery in London. The Art Institute of Chicago20 is…

LLW: I mean, it is so good.

NI: But I have to say… the Barnes is such a knockout collection. All of those museums are different, and I like them for different reasons. I always love l’Orangerie21 when I'm in France…you know, that's a really tough question.

LLW: If you had to choose a museum city, would it be London?

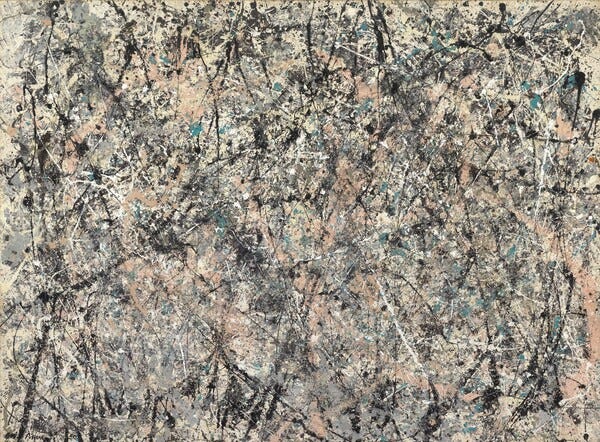

NI: When you travel a lot you get spoiled. In New York I am super happy when I'm looking at Jackson Pollock22, while in Vienna it might be Klimt23.

LLW: I’ve said it once and I’ll say it again: I love Vienna. The museums there are incredible.

NI: It’s a really hard question. That's like asking: what food would you eat for the rest of your life? <laugh>

LLW: Fair enough. How about this: What are you currently obsessed with? Is it an artist, glassware, clothing, reading some dense book, or even jogging? What can you just not stop thinking about?

NI: Obsessed might be an overstatement, but I am impressed with some of the recent Toteme24 looks.

LLW: I can relate. Why do you like them?

NI: The simplicity of their pieces. Strong recognizable designs, nothing too fussy, vaguely functional.

LLW: <laugh>

NI: I think they have some interesting ideas. That would be what I’m thinking about outside of work. During work [right now] it is probably Picasso because I'm giving a talk on Thursday in Chicago about Picasso.

LLW: Oh my gosh. Is it at the Art Institute? Or?

NI: Yeah, they have a show on his drawings right now.

LLW: You're so cool.

NI: I’m honored!

Thank you to Nancy and her team at the Barnes Foundation, particularly Director of Communications, Deirdre Maher. To learn more about the Barnes and plan your visit, see here. Also, the Barnes offers awesome online and in-person courses for the art curious among us, their classes are not to be missed.

Connecting with Nancy and learning more about the Barnes meant a lot to me. As explained at the beginning of this article, I have a special place in my heart for this institution, but as we learn in life, all of this would be nothing without people. The artwork in the Barnes collection are activated by people like Nancy and her team, and Dr. Barnes before them. Conversations about art and what it all means and why its important are significantly better when had with others, and pre-dinner drinks are always augmented by good company.

A scholar of late 19th- and early 20th-century European art, Ireson has held curatorial positions at institutions including Tate Modern, The National Gallery, London, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Exhibitions she has curated or co-curated in her specialist area include Modigliani Up Close (Barnes, 2022); Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel (Barnes, 2021); Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy (Tate Modern, 2018); Modigliani (Tate Modern, 2017); Temptation! The Demons of James Ensor (Art Institute of Chicago, 2014); Jane Avril and Toulouse Lautrec: Beyond the Moulin Rouge (Courtauld Gallery, 2011) and Cézanne’s Card Players (Courtauld Gallery, 2010). At the Barnes she manages the teams responsible for Collections and Exhibitions, including Curatorial, Conservation, Registration, Publications and Design. Ireson studied at the Courtauld Institute of Art, where she earned her BA in the History of Art, an MA in European Art 1907–1945, and a PhD on the work of Henri Rousseau.

(b.1841 - d. 1919) Pierre-Auguste Renoir was a leading French Impressionist painter

LLW is referring to the fact that Nancy is currently Deputy Director of one of the world’s most important collections of Impressionist and Post-impressionist artwork. Talk about manifesting!

The National Gallery in London, England aka one of the most fabulous museums in the world. The best part? It’s free to visit. Learn more and view their collection online here.

(b. 1870 - d. 1939) American artist born in Philadelphia, PA. Glackens was known for his contributions as a Realist painter and for being one of the founders of the Ashcan School, which rejected the rigidity of artistic beauty as defined by the conservative National Academy of Design.

(b. 1853 - d. 1890) Vincent Van Gogh was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who, despite his short life and rocky career, is one of the most influential artists in the history of Western art.

(b. 1881 - d. 1973) Pablo Picasso was a Spanish artist, perhaps the most recognizable of artists Picasso painted, sculpted, worked with prints and ceramics and even designed sets for the theater. His artwork spans many artistic periods such as Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism and Modern Art.

$20,000 in 1912 is equivalent to $643,984 - which is still a surprisingly small sum of money if you consider Glackens was able to acquire a Picasso, Monet and Van Gogh painting with it.

(B. 1893 - d. 1943) Chaïm Soutine was a French Expressionist painter of Belarusian and Jewish origins. For those Readers who have seen Mona Lisa Smile (2003) Soutine’s art is shown on Julia Roberts’ slides in an art history course to the absolute shock of her lady-students. Haven't seen? Major rainy day recommendation.

(b. 1839 - d. 1906) Paul Cézanne was a French post-impressionist painter whose work is seen as a bridge to the cubist period in the 20th century.

(b. 1859 - d. 1952) John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer. He and Dr. Albert Barnes had a close relationship over their shared interest in how people learn.

Nancy is referring to the way the Barnes Foundation’s artworks are hung and organized throughout the space.

(b. 1884 - d. 1920) Amadeo Modigliani was an Italian painter and sculptor who worked within the schools of Expressionism and Modern art.

(b. 1960) Sir Isaac Julien is a British artist and filmmaker. Presently he is also a professor at University of California Santa Cruz. Learn more about Isaac Julien and his work here.

Le Bonheur de vivre, also called The Joy of Life, was painted by Henri Matisse between October 1905 and March 1906. It resides at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, PA.

(b. 1859 - d. 1891) Georges Seurat was a French post-impressionist artist who developed techniques like pointillism which is best exemplified in his large scale painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, which hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago.

Another epic artwork, this one from the 19th century and by the hand of Seurat. He was a master in color.

James Claiborne is the Deputy Director for Community Engagement at the Barnes Foundation.

William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision, learn more about this past exhibition at the Barnes Foundation here.

The Art Institute of Chicago is top notch, excellent, a grad-A experience. Their collection boasts some incredible and recognizable American and European paintings ie. American Gothic, Nighthawks, Van Gogh’s Bedroom, Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day (just to name a few). Learn more and plan your visit here.

Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, France is a wonderful and well sized art gallery that is best known for housing The Water Lilies by Claude Monet. Learn more and plan your visit here.

(b. 1912 - d. 1956) Jackson Pollock was an American painter and critical figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement. You for sure know him, the guy who splattered and dripped and flung paint on canvases on the ground. Iconic.

(b. 1862 - d. 1918) Gustav Klimt was an Austrian painter and prominent figure in the Austrian Secession movement which was formed in 1897 and closely related to Art Nouveau. One of Klimt’s most recognizable works is The Kiss.